Martin Freeman: An open pension architecture would help retirement solutions providers play nicely with each other

We have passed many happy hours discussing the relative merits of different approaches to dealing with small pots.

The current government's preference is for a default consolidator, but it is teasing us with a lifetime provider model. Others have chipped in with calls for "magnetic pensions" or other intriguingly named solutions.

These solutions are basically the same thing. Arguing over the consolidation model is like the Lilliputians arguing over which end of the egg you should break open. Because we need to build pretty much the same technology regardless.

A National Pensions Grid

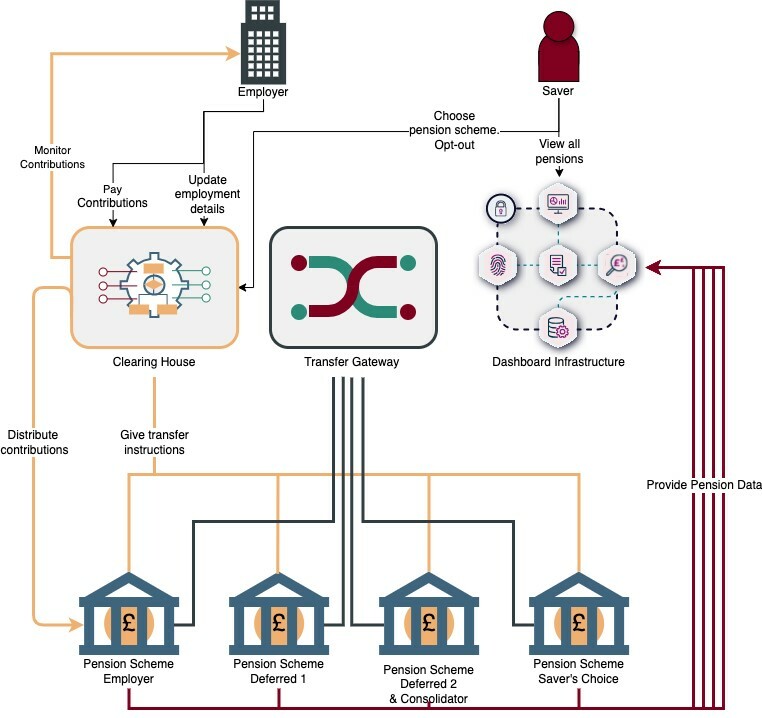

What we need to build amounts to a National Pensions Grid. To construct this, we need to do three things:

- Identify the pensions a saver has. The dashboard has given us a great foundation. There are legal and technical implications for using something for a different purpose than what it was built for, but we have a great start.

- Move money between schemes securely, quickly and easily. This bit we don't have as it is not universal. Let's call it a "Transfer Gateway". It would take instructions and move pensions money instantly and seamlessly.

- Define the rules that determine where a saver's contributions should go, or if a pot should move from one provider to another. These rules could be administered by a clearing house that knows if an individual has chosen a scheme or opted out of pension saving, who they work for, how much they earn. It would act like a traffic cop, directing contributions and pots to whichever scheme the rules say they should go to.

The point is that the rules don't really determine what we need to build, and they can change over time. This means we can evolve the approach, implementing the consolidator model and adding lifetime provider afterwards, for example.

We often frame our debates in terms of binary choices; pot follows member or lifetime provider, defined contribution (DC) or collective DC, inertia or engagement. But we need a multi-factorial approach where we can support motivated individuals who want to make choices whilst at the same time having effective default approaches for those who do not.

Here's what a National Pension Grid could look like. It's conceptual, and you could divvy up the responsibilities differently, but it shows the main idea.

It could enable employers to direct contributions to their employees' chosen schemes without increasing their administrative burden. If anything, it could reduce it, and make it easier for them to change schemes, as well as making it easier for members to transfer their funds. It could centralise contributions monitoring, removing that duty from schemes and allowing them to focus on service rather than policing. By removing the inertia, providers can be more responsive to their customers.

A long time in the making

This is a radical approach that could take 10-15 years to deliver. But pensions are a long-term business. We need to think like a utility, seeing investment as akin to building roads, broadband or water infrastructure. Otherwise, we'll be hostage to our sclerotic systems and decrepit data, and never be able to transform our industry to serve members better.

The opportunities an open National Pensions Grid offers are exciting and terrifying. It breaks open the monolithic business model where each provider offers a full suite of services, in a silo, duplicating each other and battling to be the one scheme that grabs the member's attention.

An open pension architecture would help retirement solutions providers do what they have struggled to do so far; play nicely with each other. Share information and move funds as an individual wants, rather than relying on friction and inertia to hoard it. Not all individuals will want this, but it can be complementary to default journeys for the disinclined.

The reason this opportunity is terrifying is because it breaks the industry's value chain and reassembles it by putting individuals at its heart rather than employers.

Do employers really act as consumer champions?

There is an argument that employers act as a consumer champion, providing the oversight that ensures that pension schemes respond to market demand, but these interests are not always aligned.

Employers may place more value on the interests of employees than those of ex-employees. They may accept higher member charges if it decreases their costs. They may be reluctant to pay more for at and post retirement services because they relate mainly to people who may not have worked for them for decades.

As the defined benefit pensioned, job-for-life world disappears, pensions have become more commoditised. This means that their power as an attraction and retention tool diminishes. I have been involved in many recruitment exercises, in the pensions industry, and not once has the candidate asked about the pension, let alone used it as part of the negotiation.

Most employers are small and do not have the resources to consider what pension scheme is most appropriate. Pension consultants deal with a self-selecting set of large, motivated employers who value pensions to such an extent that they are happy to pay for a consultant. About 0.02% of employers have 500 or more employees, and I suspect this is the pool from which employee benefit consultants' clients are drawn.

And this discussion doesn't even touch the 4.25 million people who are self-employed, representing about 13% of the workforce. An emphasis on individuals puts them in the pensions fold, from which they are currently excluded.

So, the market needs to evolve. It needs to move on from the parental, job-for-life employment model on which it is still predicated, and recognise the 12 jobs per working life, portfolio careers, gig-economy world that we live in now. That gives individuals agency when they want it, and supports those who don't.

It will take time, and the two worlds will co-exist for a long time. But it can only happen if we have the national infrastructure to support it. It will enable providers and consumers to interact more directly. Over time, the proportion of individuals who feel a connection and an ownership of their retirement savings will grow, and the market will shift from an employer centric to a consumer centric dynamic. And then, innovation and true consumer focus could flourish.

In the meantime, the answer to "which should we do, pot follows member or lifetime provider?" is "yes, both. They're pretty much the same thing."

Martin Freeman is a director at Pensio