Key points

- The crisis has led to an increased focus on a range of sectors, not least energy and defence

- Particular issues being rethought are whether nuclear should be seen as a source of green energy

- There is also a renewed debate over the extent to which schemes should exclude the defence sector

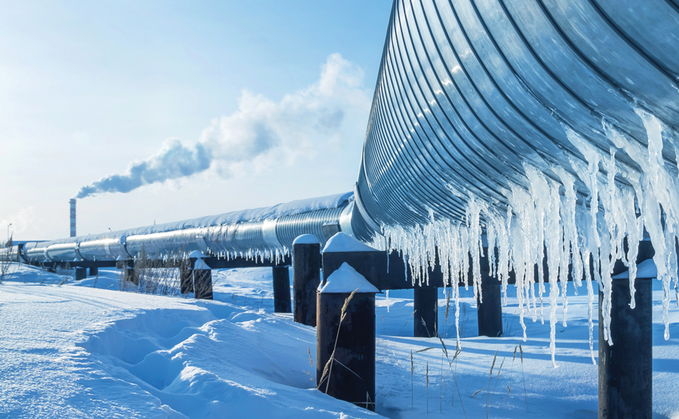

Russia's invasion of Ukraine has pushed energy security to the top of the political agenda, with European governments scrambling for alternative sources of fossil fuels. This sparked concern about a negative impact on the pace of decarbonisation.

The search for alternative sources of hydrocarbons has meant ideas that were previously deemed bad choices are back on the table, including North Sea oil, the use of coal and a call for more fracking.

Some in the sustainable investment community worry this renewed love of hydrocarbons threatens to derail the net-zero commitments made during last year's COP26.

But the noise of the headlines is a distraction − the renewable energy agenda is unchanged.

Lane Clark & Peacock partner Dan Mikulskis says: "The UK was already planning a huge switch to sources of renewable energy."

The UK is aiming to generate 100% of its electricity from renewables by 2035. It's also wants to increase its offshore wind capacity to 40GW by 2030, up from around 11GW in 2021.

What has changed over the past few weeks, however, is the importance of national security. Renewity co-founder and chief investment officer David Hunter says: "Energy markets should always be regarded as national security assets."

Mikulskis adds: "We don't, however, have to choose whether to prioritise energy security or sustainability - a switch to greener energy supports greater energy security."

While the switch to greener energy is underway, it will, however, take at least a decade to achieve it. Mikulskis says: "If we need a short-term source of energy there are not many other options to switching oil and gas supplies or even turning back to coal."

Rather than viewing the West's spurning of Russian hydrocarbons as a threat to sustainability, this desire for energy security should be a force for good. Mikulskis says: "This should bolster public support for the switch to renewables."

Redington head of stewardship and sustainable investment strategy Paul Lee agrees: "The renewed focus on national security should provide an impetus for us to generate power without having to rely on autocratic regimes for oil and gas."

Maintaining national security

Even if the West manages to reduce its dependence on external hydrocarbons, national security will remain a live concern.

For example, batteries are highly reliant on metals such as lithium, nickel and cobalt, which are currently in more limited supply in the West. China has also become the world's largest producer of solar panels.

It would be odd to view energy assets as an important part of national security, only to switch from a reliance on Russian hydrocarbons to one on Chinese technology and rely on more dubious mining practices.

Hunter says: "While China has captured much of the African market for rare earths with cheap loan deals, the US and the West now realises they need to exploit sources in their own territories and diversify."

In addition, Australia is a key source of uranium so this should be a reliable source for nuclear power, adds Lee.

And while China currently supplies most of the world's solar panels it's far from certain this will remain the case, with US and Europe likely to start onshoring manufacturing, says Lee.

Hunter agrees: "Globalisation reached its peak in 2015-2016, with many trade and economic policies now trending back to renationalisation."

One of the fastest-growing trends is the re-shoring of manufacturing to developed markets. Hunter says: "This is partially to due to sustainable investing and economic concerns but also awareness of the importance of energy security is likely to accelerate this trend."

Nuclear rides to the rescue

A renewed focus on energy security has not just created a need to switch to short-term hydrocarbons but has also forced the issue on nuclear.

Mikulskis says: "People have long said that nuclear needs to be part of the renewables plan but governments have resisted it up to now because it is politically difficult."

While solar and wind can provide good sources of power, they are intermittent. And until battery technology has evolved sufficiently to store excess power, they will not be able to provide consistent power supply.

Hunter says: "Even with the best possible transition to renewables, we will still have to rely on more traditional energy sources such as nuclear and hydrocarbons."

But even if providing nuclear became less politically divisive, it will take time to build new power stations - it could take as long as 10 years.

All the UK's existing nuclear reactors will have closed by 2028, with the exception of Sizewell B, with only currently being constructed, Hinkley Point C, set to enter operation in that time frame.

Nuclear accounted for 16% of domestic UK generation in 2020, down from 21% in 2016.

A funding mechanism for EDF's two-unit Sizewell C project has yet to be finalised.

Impact on EU taxonomy

The focus on energy security has, however, calmed some of the debate surrounding the EU taxonomy, which recently created furore when the final version included both gas and nuclear as sources of green energy.

Lee says: "The fallout from the Russian invasion adds weight to the taxonomy deciding nuclear can be seen as sources of green energy."

But even if the debate should subside, the taxonomy may be of limited use.

Investors do want a way of identifying climate solutions and the taxonomy could have been a real help but in practice it has not worked out that way. Mikulskis says: "The search is still on to find ways to identify these solutions at a portfolio level."

Collaborative investor groups like the Institutional Investors' Group on Climate Change may be well placed to offer a framework here, he adds.

But this does not mean the taxonomy should be revisited. Mikulskis says: "Too much energy has already been spent on the taxonomy - it's not as influential as people think when it comes shaping how people decide to invest."

It's likely, however, that investors will select sustainable investment products that include nuclear but don't include gas, he adds.

Defence stocks

Questions have been also been raised about whether investors should have excluded not only manufacturers of egregious weapons, such as cluster bombs, but also conventional weapons.

Mikulskis says: "We need to get away from the idea that sustainable investing is putting stocks into two buckets labelled ‘good' and ‘bad' then playing back-seat portfolio manager and asking if those labels are correct."

In other words, sustainable investing is not about imposing values on how your portfolio is designed but about identifying hidden risks and deciding how much positive change you want your investments to make.

"It's particularly important for pension schemes to think about risk management because of their fiduciary duty to separate them from ethical considerations," says Mikulskis.

Mikulskis says: "There is, however, an important question to be asked about the role of exclusions in portfolio design and whether they make sense."

Currently investors can select from those funds which either don't offer any exclusions, those that exclude only controversial weapons and those that also exclude all conventional weapons. Mikulskis says: "One of the most common choices is controversial weapon exclusions."

The bulk of pension scheme equity investment is made via passive equities. Most choose to add sustainability to their portfolios by tilting these investments towards stocks with high ESG scores and excluding low ESG scores.

It is rare for a pension scheme to exclude an entire sector - apart from tobacco stocks - as this would cause significant deviations from index performance.

Mikulskis says: "We don't advise schemes to focus on sector exclusions as the main part of their ESG policy as it's better to be able to take a balanced view and tilt instead."

For those investors wanting to make positive change as well as thinking about reducing risks, there are plenty of different mechanisms to do this effectively.

That can include, for example, ESG ratchets on private investments as well as linking strategies to achieving sustainable development goals. These are all more sophisticated ways of achieving positive change than blanket exclusions.

Charlotte Moore is a freelance journalist